🏠 Homeward Bound

FIRE BTC Issue 61 - Is housing affordability really a crisis?

This week’s piece was inspired by a recent conversation on X Spaces that I joined. What began as a broad discussion about bitcoin and markets gradually turned into a heated exchange about the housing affordability crisis.

As the debate unfolded, I suggested that long-term trends do not remain static—and that it may not be reasonable, or even desirable, to assume that the specific path previous generations used to build wealth through housing should persist indefinitely.

The economic environment has changed. The opportunity set presented to current generations has changed. And when those conditions shift, the strategies that made sense in the past deserve to be reexamined rather than reflexively defended.

Below is a link to the conversation if you’d like to listen back:

I thought I would expand on my thoughts through the newsletter this week, and run some numbers to support my claims.

⚙️ America’s default wealth engine

For much of American history, ownership of land and housing has been foundational to economic security. Long before the phrase American Dream was coined, the ability to acquire and own land represented independence, stability, and a durable store of wealth in a growing nation. As the United States industrialized and urbanized, this ethos carried forward into homeownership, which became a defining feature of middle-class prosperity.

The widespread adoption of the mortgage fundamentally reshaped how Americans accessed housing. Mortgages introduced leverage, allowing households to control a large, scarce, and historically appreciating asset with a relatively small amount of upfront capital. As home values rose, returns on the homeowner’s initial equity were amplified relative to the down payment. Over time, this made homeownership appear not only safe, but financially compelling.

Throughout much of the twentieth century, this model worked well. For many families, home equity became the central pillar of household net worth and, in practice, the primary mechanism for long-term savings. Previous generations were often able to purchase homes earlier in life, service mortgages comfortably, and benefit from decades of rising prices and inflation eroding the real value of fixed-rate debt. This created a powerful financial tailwind that shaped expectations about how wealth was built in America.

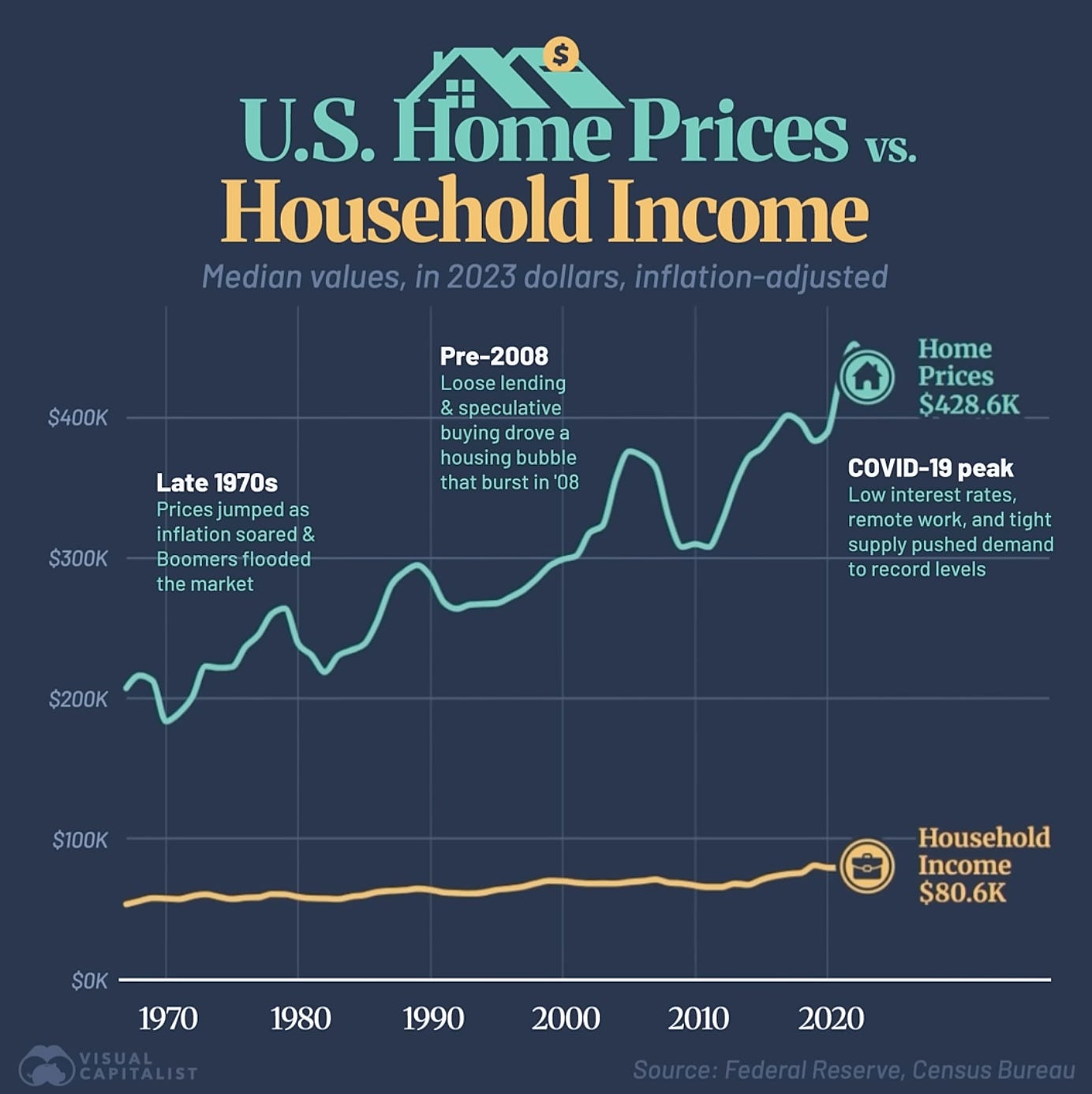

Against that historical backdrop, it is easy to view today’s housing affordability crisis as cause for deep concern.

If homeownership has long been a cornerstone of household wealth—and if that path is now increasingly unattainable—does that imply that future generations will be structurally poorer, permanently constrained to renting? Will they miss out on the same wealth-building opportunities their parents and grandparents relied upon?

There is little doubt that the fiat monetary system has played an important role in driving housing costs higher. The availability of cheap money and abundant credit has inflated asset prices broadly, housing included. Lower interest rates increase purchasing power, bid up prices, and embed higher valuations into the system over time.

But monetary policy is not the sole driver. Demographics, household formation, migration patterns, and supply constraints all contribute as well. In the mid-twentieth century, many areas of the United States that are now considered highly desirable were still sparsely developed.

Previous generations had access to an opportunity set that no longer exists in the same form. Instead, younger generations face a different one.

At the same time that housing has become more expensive, the nature of work and wealth creation has changed dramatically. It is now easier than ever to work remotely, start a business online, and reach a global market with relatively little upfront capital. Digital products, services, and platforms have lowered barriers to entry in ways that were simply not available to prior generations.

This raises an important and underexplored question: if housing affordability continues to deteriorate, is that outcome necessarily catastrophic? Or does it simply force a shift away from one historical wealth-building path toward others that may be just as powerful?

Complicating this discussion further is a widespread misconception about housing returns. Levered homeownership often feels like it outperforms the stock market. A modest down payment appears to grow into a large amount of equity, creating the impression that housing is a superior investment. But this intuition is misleading.